The continued relevance of Bengal art

A recent show in New Delhi underscored the importance of good art, and that Bengal continues to be at the forefront of churning it

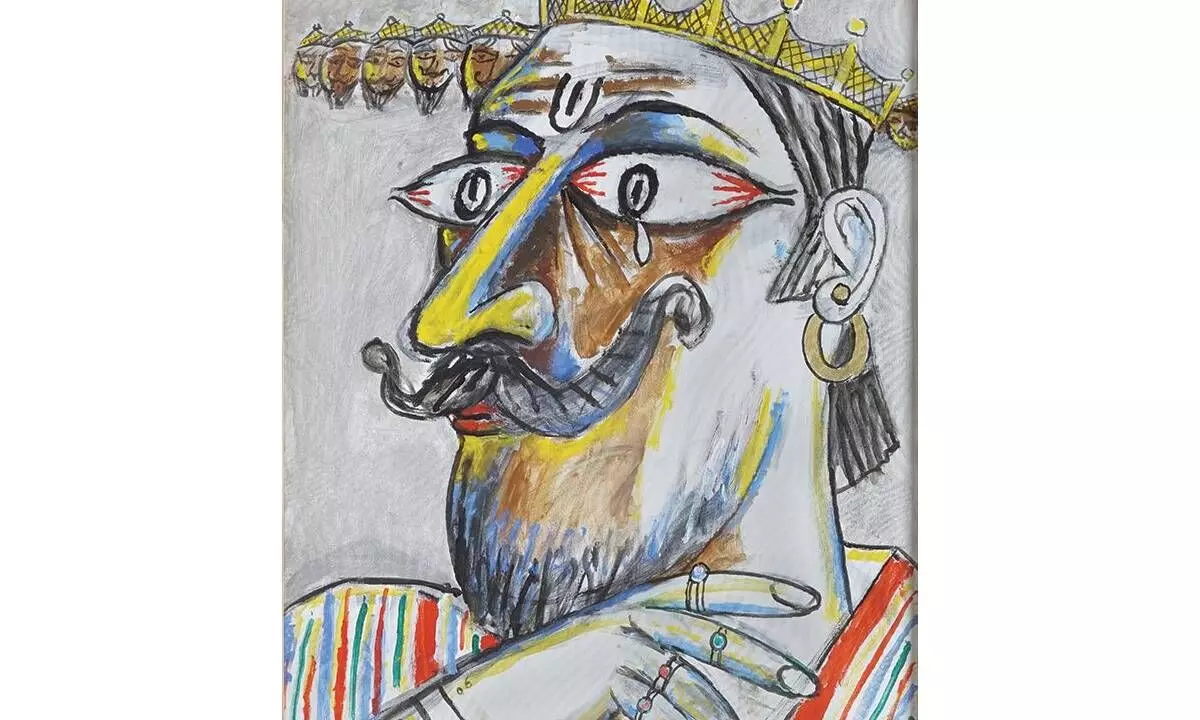

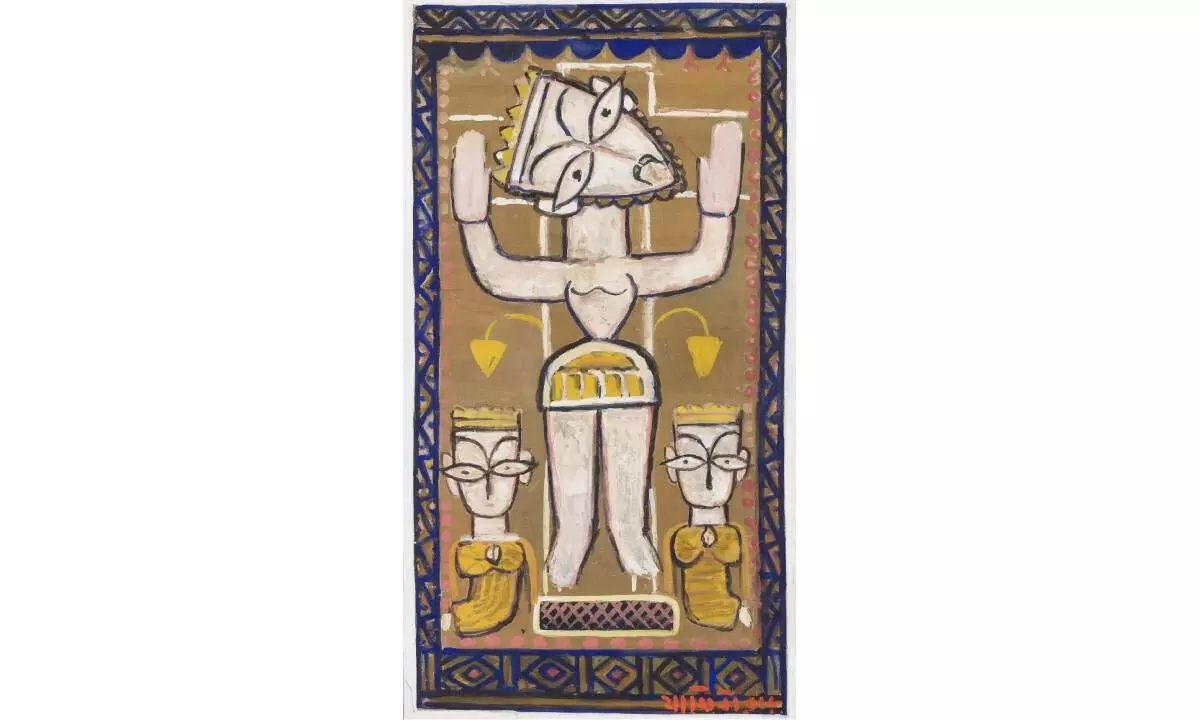

image for illustrative purpose

The distinguished Bikaner House in New Delhi recently hosted a show by Aakriti Art Gallery, titled ‘Bengal Beyond Boundaries’, which got the city talking, and delighted. The reason was not far to seek but evident at the display of the works curated by Uma Nair. It was a selection that stunned with its breadth, presenting a studied evolution of modern art from the state of Bengal.

Geographical markers for art in contemporary times are fraught with complications. Globally, contemporary artists, especially, are known to take pains at discarding any hints that may get their works clubbed into a particular regional category. From the current darling of Asian-origin western contemporary art, Salman Toor — who is based in New York and is an American artist of Pakistani origin — to India’s very own Subodh Gupta — inarguably the most well-known and successful contemporary artist from South Asia — artists try hard in very apparent ways. Yet, their art is but one aspect of their personality, which cannot be divorced from their South Asian-ness.

At the same time, it is the geographical roots of the artists that lend their art an edge to stand out in the crowd, which is a back-handed way of acknowledging the importance of their roots even while turning their back on it steadfastly.

What is Bengal Art?

In this scenario, it is worthwhile to try and understand what is Bengal Art, beyond boundaries, as the recent exhibition tried successfully to showcase.

Is Bengal art the one created by artists of Bengali ethnicity? Not necessarily. Is Bengal art the one created physically in the state of Bengal? Again, not necessarily. Is Bengal art the one dealing with ‘Bengali themes’ (whatever that may be)? No. Is Bengal art the one created by students whose teachers were Bengalis, or who, perhaps, studied at an art institution in Bengal? Not necessarily.

Bengal art is actually all of the above and so much more. The term held great significance when it was first coined. Bengal School was a genre of newly-emerging authentically Indian art — as opposed to European/ British academic art that was being taught to Indian students, pioneered by AbanindranathTagore, (whose name always comes hyphenated as the nephew of Rabindranath Tagorethough he was a stalwart in his own right). He broke away from British academic realism to focus on ancient Indian art heritage through murals of the caves at Ajanta, and created an idiom that was authentically rooted in the soil of the Indian subcontinent. It emerged from the Indian School of Oriental Art that Tagore founded in 1907. Soon, all art created by the adherents of this school of thought and practice came to be known as Bengal art.

By the time Santiniketan emerged as a fount of learning, original thought in creating visual art had taken strong root among Indian artists and even moved beyond the hoary Ajanta aesthetics, connecting more with the living artistic traditions in rural India. Nandalal Bose, a pupil of Abanindranath Tagore, was a pioneer of this generation of artists. What he created was also Bengal art.

A few years later, artists like Paritosh Sen, Somnath Hore, KG Subramanyan, and even later, A Ramachandran, Bikash Bhattacharjee, KS Radhakrishnan, also became ‘Bengal’ artists. As one would notice, not all the artists listed above are of Bengali ethnicity, but were trained in Bengal, by Bengali teachers, and acquired an aesthetic that was individual but distinctly Bengali in attitude, perceptibly carrying a bit of their teachers’ persona in their art.

All of the above were/ are Bengali artists by virtue of a combination of several factors. What sets them apart from art produced in any other region is the distinct desire to break free of tradition and try something new, and creating a strong identity for the art of times in doing so.

‘Bengal Beyond Boundaries’

The show by Aakriti Art Gallery in New Delhi, therefore, was seminal for making a brave and successful attempt at presenting this essentially Bengali sense of aesthetic, that is not unique but definitely one of the several unique strands of modern Indian art found in different regions of India.

The exhibition featured works from Abanindranath Tagore and Nandalal Bose on one hand to Jogen Chowdhury, Sunil Das, Ganesh Haloi and Shyamal Dutta Ray on another; from Jayashree Chakravarty, Shuvaprasanna, Shipra Bhattacharya and Jayasri Burman, on one end to Akhil Chandra Das, Chhatrapati Dutta, Prasenjit Sengupta and Tapas Biswas on the other; and many, many more. Unfortunately, it is beyond the scope of this write-up to describe all the works that were part of the exhibition, much as this writer would want to.

It is also a pity that the exhibition did not last long enough, for it was after a long while that a brilliantly, and tightly curated show around a ‘much-heard-about-but-little-understood’ theme was mounted in the city.

Learning from Bengal Artists

If there is one takeaway from the universe of art in Bengal, it is its capacity to break free of stereotypes, to push the envelope, to discard rules etched in stone, and to forge a totally new path for generations to follow. Artists from Bengal have done it repeatedly. Abanindranath Tagore did it and gave birth to the first flush of ‘swadeshi’ in the arts, at a time when the entire Indian sub-continent was beginning to feel pride in the idea of ‘home grown.’ Nandalal Bose did it by repudiating his western training in art and picking up local styles and flavours to create a uniquely individual variety of art distinctly rooted in traditional ethos. Scores of artists from Bengal have followed in these hallowed footsteps, which the exhibition, ‘Bengal Beyond Boundaries’ presented through its showcase spanning generations.

(The writer is a New Delhi-based journalist. She blogs at www.archanakhareghose.com)