Lord Rama's enduring appeal in art and auctions

Lord Ram and the Ramayana continue to hold immense significance in Indian culture, evident in their enduring presence in art forms across eras and their value at international auctions

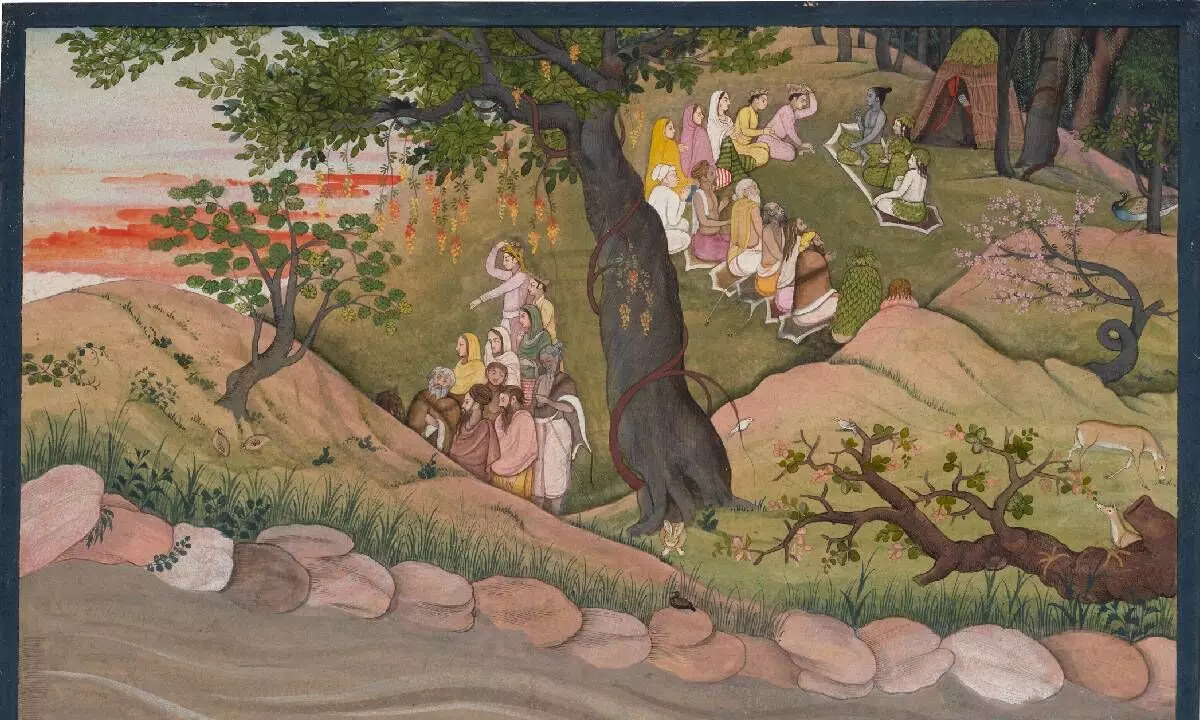

image for illustrative purpose

In this epochal moment for Lord Ram, it would be insightful to see how the deity surrounded by controversies not of his making, and the religious scripture that details his life story, the Ramayana, have fared in the world of art and at the auctions.

It goes without saying that Lord Ram and the entire pantheon of Ramayana deities have remained a popular subject for Indian artists, not only in pre-modern times when religious art was the most prominent form of art, but also in modern era, when artists consciously shunned religious themes to explore the wide world beyond. But the Ramayana, as also the Mahabharata, are not just religious texts but time-tested ancient scriptures on the art of living that a majority of this country continues to abide by, consciously or sub-consciously. It’s not a surprise, then, that the Ramayana paintings, either featuring popular episodes, or individual deities associated with the epic, have been created by every generation and in every era of Indian art.

Two of the most popular Ramayana paintings from the modern era—series of paintings featuring different deities and episodes—that immediately come to my mind are those by MF Husain (1913-2011) and Laxman Pai (1926-2021).

MF Husain’s Ramayana Paintings

It’s a pity that most of the lay admirers of art are likely to remember the late MF Husain for having courted controversy with his questionable portrayal of Hindu deities. What is not commonly known is the story of how he came around to painting a series on the Ramayana. Here, I would like to quote from the book, MF Husain: A Pictorial Tribute by Pradeep Chandra (New Delhi: Niyogi Books, 2011), ‘He recalls with fondness the childhood memories of listening to the Ramayana with rapt attention... He says, “As a child in Pandharpur, and later, Indore, I was enchanted by the Ramlila. My friend, Mankeshwar and I were always acting it out… The Ramayana is such a rich, powerful story, as Dr Rajagopalachari says, its myth has become a reality.” Many years later, he got a chance to express himself on his favourite epic. The year was 1968. Husain met Dr. Ram Manohar Lohia in Hyderabad who suggested that he paint the Ramayana.

He says, “I painted 150 canvases in eight years. I studied the Valmiki and Tulsi Ramayana (two of the most popular versions of the Ramayana). In my view, Valmiki’s version is more emotional. To discuss my doubts, I called on the pundits of Benares (Varanasi). Ujjain’s world famous astrologer Pandit Suryanarayan Vyas and litterateur Dr. Shivmangal Singh Suman were some with whom I debated for hours. When I was doing this, some hard line Muslims asked me why I don’t paint Islamic themes. I asked them whether Islam has as much tolerance; if I make a small mistake in calligraphy, they would tear my canvas.’

The other popular modern rendition of the Ramayana is that by the well-known artist from Goa, Laxman Pai, who made watercolour paintings on the epic, right from the birth of Ram and other princes, his marriage to Sita, his exile, victory over Ravana, and eventual return to Ayodhya.

There have been several other modern artists who have essayed the theme of the Ramayana—including endearing renditions by Jamini Roy (1887-1972)—but the list would be too huge to accommodate in the scope of this write-up.

Ramayana Paintings at the Auctions

Historical Ramayana paintings, especially from the Mughal times when the art of painting—especially miniature painting—was nurtured by royalty and achieved an apogee, have been a recurring feature at the international auctions and almost always command good prices, going beyond pre-auction estimates. For those not initiated, the earliest Ramayana paintings were the illustrations in manuscripts commissioned by the Mughal emperor Akbar, who got both the Ramayana and the Mahabharat translated into Persian and illustrated for the awareness of Hindu religion and culture among the empire’s Muslim elite, according to Konrad Seitz in his book Origins of Orchha Painting: Orchha, Datia, Panna: Miniatures from the Royal Courts of Bundelkhand (1590-1850), Vol. I (New Delhi: Niyogi Books, 2022), as quoted in various news sites.

One of the most valued Ramayana paintings at the auctions remains an 18th century miniature that sold for $315,000 (approx. Rs 2.6 crore at current exchange rates) at a Christie’s auction in New York in September 2022. Titled, A Painting from the ‘Bharany’ Ramayana: Rama, Sita and Lakshmana at Panchvati, this miniature measures 20.6 x 31.1 cm. (8 1/8 x 12 ¼ in.) and came to the auction table from the John C. and Susan L. Huntington Collection, Columbus, Ohio, U.S.A. It is attributed to the first generation from the atelier of renowned miniaturists Nainsukh and Manaku of Kangra or Guler, Punjab Hills, and dated to circa 1775. It’s pre-auction estimate was $100,000 - $150,000 (approx. Rs 82 lakh – Rs 1.2 crore).

Another high-value Ramayana painting at the auction was an illustration featuring the first combat of Sugriva and Bali, an ink on paper work from circa 1710-1720, from Nurpur or Mankot (in present-day Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand respectively), that fetched £156,250 (approx. Rs 1.6 crore at current exchange rates) at a Sotheby’s auction in October 2017. This price was achieved against an estimate of £20,000 - £30,000 (approx. Rs 21 lakh – Rs 31 lakh).

It’s interesting that the depiction of the characters from the Ramayana in the Mughal miniatures is quintessentially Mughal, quite similar to the depiction of royal personages of the time, and can be easily mistaken by an untrained eye for the royalty of the time, either Mughal or Rajput.

These Ramayana paintings from India’s medieval age, in that sense, are a pleasant expression of how different cultures were coming together to create a wholesome image of the people of the land, a cultural commingling that does not have a parallel in the world, and one that would undergo yet another churn with the arrival of the British colonisers a few centuries later.