Why Dhurandhar signals Bharat’s entry into competitive narrative warfare

Over the past decade, multiple governments across regions have weakened or collapsed without formal declarations of war

Why Dhurandhar signals Bharat’s entry into competitive narrative warfare

Fifth-generation warfare (5GW) is no longer a theoretical construct confined to military journals or strategic think tanks. It is a lived reality shaping geopolitics, international relations, and domestic political outcomes across continents. At its core, 5GW moves the battlefield from land, sea, air, and cyberspace to the human mind—where perception, belief, and narrative dominance matter more than conventional firepower.

Unlike traditional warfare, 5GW does not rely on tanks crossing borders or fighter jets violating airspace. It operates through information operations, psychological influence, cultural instruments, economic leverage, and the exploitation of social fault lines. The rise of social media has dramatically accelerated this shift. Governments, organisations, and transnational interest groups can now bypass institutions altogether and communicate directly with populations—often through selective framing, amplification of grievances, or outright disinformation.

The outcomes are no longer abstract. Over the past decade, multiple governments across regions have weakened or collapsed without formal declarations of war. In the subcontinent, developments in Bangladesh—regardless of their internal political drivers—demonstrate how sustained narrative pressure, amplified by digital ecosystems, can accelerate institutional delegitimisation and leadership isolation.

In the modern age, a nation does not need to fire a bullet to achieve outcomes that once required invasion.

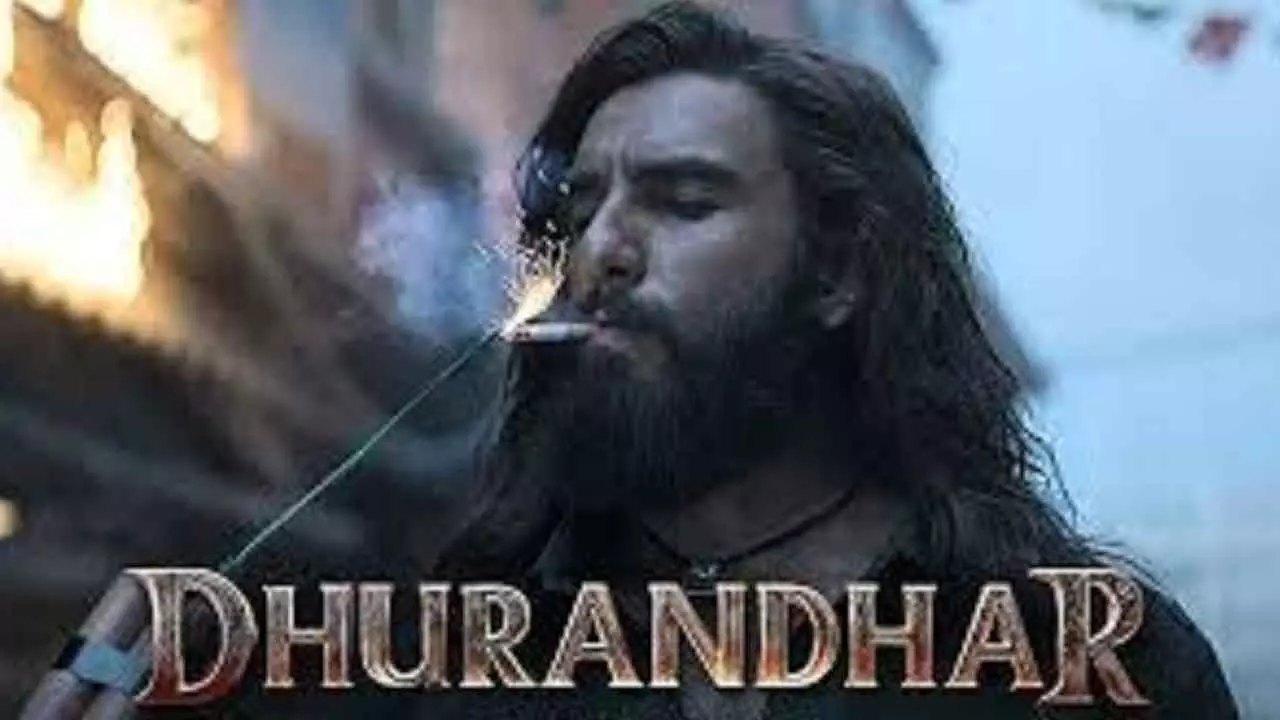

It is against this strategic backdrop that the recent Bollywood film Dhurandhar must be viewed—not merely as entertainment, but as a cultural event with geopolitical consequences.

Dhurandhar and narrative warfare

Dhurandhar is not India’s first politically charged film. But it is among the rare few to generate visible international reaction beyond domestic debate. The strong response within India, the sharp pushback from Pakistan, and bans or restrictions in parts of the Middle East point to something deeper than cinematic controversy: the film disrupted existing narratives.

In fifth-generation warfare, narrative-setting is foundational. The objective is not immediate persuasion but framing—establishing a storyline that shapes how events are interpreted. Once seeded, the narrative is amplified through media ecosystems, opinion leaders, and public discourse. The population then does the rest—debating, polarising, reinforcing, and exporting the narrative organically.

The reaction to Dhurandhar illustrates this mechanism in action. The controversy itself became the amplifier. The bans and denunciations validated the film’s impact far more effectively than box-office numbers ever could. Whether one agrees with the film’s perspective is immaterial. Strategically, what matters is that an Indian narrative compelled external actors to respond.

That compulsion—forcing engagement rather than being ignored—is a defining characteristic of effective fifth-generation warfare.

This does not imply state orchestration or deliberate strategic intent behind the film. In 5GW, impact matters more than design. Effects often precede doctrine.

Lessons from the Masters: China and Hollywood

If there is one country that grasped cultural narrative warfare early, it is China. By the early 2000s, Beijing recognised that global perception—especially in the West—was shaped disproportionately by Hollywood rather than by policy papers or diplomatic statements.

China’s approach was neither loud nor crude. It was capital-driven and structural. Chinese investors, financial institutions, and production partners embedded themselves deeply within Hollywood’s financing ecosystem. Studios seeking access to the Chinese market—one of the world’s largest—quickly learned that scripts, character portrayals, and geopolitical framing carried consequences.

The shift was gradual but unmistakable. Over two decades, China’s on-screen image evolved from a peripheral or exotic backdrop to that of a responsible stakeholder, technological powerhouse, and indispensable market. Films increasingly avoided portraying China as a villain. Chinese cities, technologies, and characters were depicted positively or neutrally. Major franchises adjusted storylines to ensure China appeared either supportive or strategically invisible.

This was not accidental. It was strategic

Ironically, despite China’s limited real-world combat experience in recent decades, popular culture contributed to a widespread perception of overwhelming Chinese military and technological superiority. For global audiences, belief was shaped less by defence assessments and more by visual storytelling.

This is fifth-generation warfare at work—where perception routinely outpaces reality.

Bharat’s reality check

India’s own experience offers a counterpoint. The 2020 Galwan clash punctured the myth of absolute Chinese military invincibility, demonstrating that narrative power can collapse when confronted by reality. But such moments are rare—and costly.

Strategic communication exists precisely to avoid kinetic confrontation by shaping perceptions in advance.

Dhurandhar suggests that Bharat is beginning—perhaps unintentionally—to enter this domain. Not by fabricating myths, but by articulating its own security experiences and strategic anxieties.

India does not need to manufacture stories. Its modern history—intelligence operations, diplomatic pressures, asymmetric threats, and counterterrorism challenges—provides ample material. What it has lacked is systematic, sustained narrative projection.

Bollywood: Asset or liability?

One successful film does not constitute a strategy.

If Bollywood is to function as a serious component of Bharat’s narrative ecosystem, structural reform is unavoidable. The industry remains constrained by entrenched networks, opaque financing, and creative gatekeeping. Globally fluent writers, producers, and directors—particularly those willing to engage with strategic themes—often struggle to break through.

This is where policy intervention matters. Entertainment is not merely cultural expression; it is economic infrastructure and strategic capability. A government-backed fund supporting creative startups, OTT ventures, and research-driven storytelling studios would serve multiple objectives: employment generation, export revenue, and strategic communication.

Countries that understand fifth-generation warfare do not leave narrative production entirely to market forces—or to chance.

Why Hollywood still matters

For global narrative influence, domestic platforms are insufficient. Hollywood remains the world’s most powerful storytelling engine. If India seeks to shape perceptions across Africa, Latin America, Europe, and Southeast Asia, it must engage where narratives scale globally.

This requires capital at a level only large Indian conglomerates can deploy. If national security is a stated priority, the government should consider incentivising such investments—through tax benefits or structured frameworks, similar in spirit to CSR—focused on cultural diplomacy and strategic communication.

This would not be propaganda. It would be competitive narrative positioning—something every major power already practises, quietly and consistently.

The internal front

No discussion on fifth-generation warfare is complete without acknowledging the internal dimension. Former National Security Advisor Ajit Doval has repeatedly warned that internal fractures represent the greatest vulnerability in modern conflict. External threats are visible; internal subversion is subtle, adaptive, and harder to counter.

Fifth-generation warfare thrives on exploiting internal divisions—political, social, and ideological. It weaponises dissent, distrust, and institutional fatigue. Recognising this reality is not about suppressing debate. It is about understanding how adversarial narratives hijack legitimate discourse and repurpose it for strategic effect.

Ignoring this dimension does not preserve democracy; it leaves it exposed.

The road ahead

The lesson from Dhurandhar is not that cinema replaces diplomacy or military power. It is that narrative power now operates alongside them.

Bharat needs sustained, high-quality storytelling—films and series that are researched, credible, and reflective of its worldview. Not jingoistic fantasies, nor escapist formulae, but narratives grounded in reality and strategic context. Unlike others, Bharat does not need to invent history. It needs to tell its own story—consistently, confidently, and at scale.

In twenty-first-century geopolitics, wars often begin in minds long before they reach borders. Those who control the story frequently shape the outcome. As India’s national security leadership has observed, history is written by those who prevail.

In the age of fifth-generation warfare, narrative is no longer a by-product of power. It is power.

(The author is Founder of My Startup TV)