What's Kafkaesque all about, let's find out

The truly Kafkaesque part of living in a dysfunctional society is the sense that protest is dumb, futile or both, the recognition that direct confrontation is ineffective

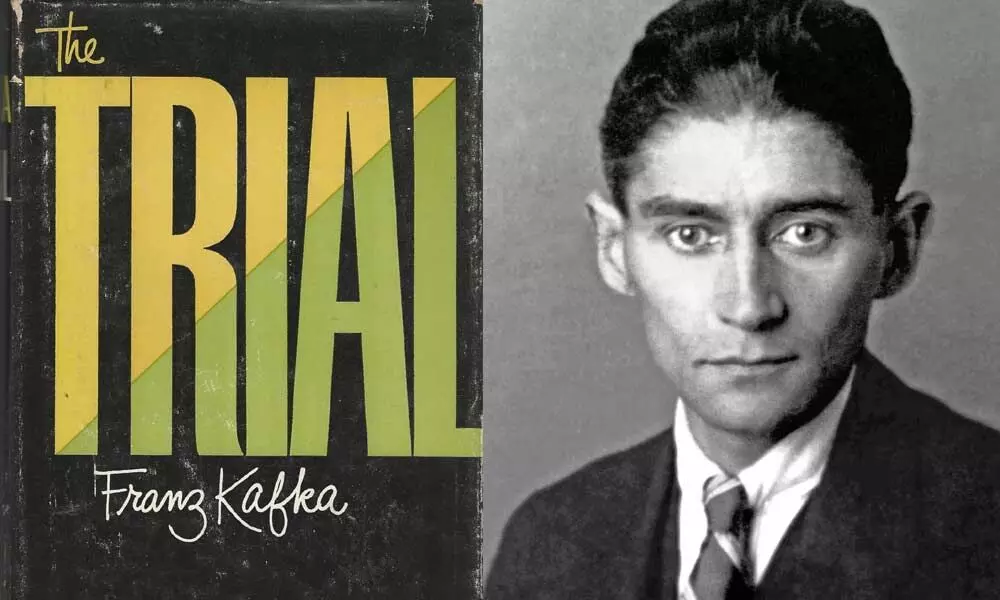

image for illustrative purpose

All the trials described as "Kafkaesque" feature both a specific accusation and a specific, transparent if wrongheaded goal pursued by the trial's organizers

AFTER handing in to the publisher my Russian translation of Franz Kafka's "The Trial," I feel as if I'm being stalked by an adjective: "Kafkaesque." Depending on how you define it, it's either one of the most misused or most relevant words in today's world.

In recent days, "Kafkaesque" has been applied to the YouTube meme of a lawyer appearing in Zoom court in a virtual cat mask, the story of an Indian shepherd imprisoned in Pakistan for alleged spying, an immigration case in Australia, the general state of affairs in Sri Lanka, the idea of turning Czech pubs into political party offices so they couldn't be closed as part of the Covid lockdown, the mistreatment of an Albuquerque high schooler by local police, a jail sentence for an investigative journalist in Montenegro and - by the French foreign minister - to the jailing of Russian opposition leader Alexey Navalny immediately upon his return to Russia after being treated in Germany for poisoning.

According to Google Trends, global interest in "Kafkaesque" peaked sharply twice in the last two years. In September 2019, the peak coincided with the Merriam-Webster dictionary's nomination of the term as one of the "words that defined the week" after a story in the Washington Post applied it to then-President Donald Trump's management style. In August 2020, the spike was almost certainly caused by Elon Musk's much-liked and much-quoted tweet: "Bureaucracy is inherently Kafkaesque."

The dictionary definition - "having a nightmarishly complex, bizarre, or illogical quality" - lends itself to the broadest application. That definition rings hollow to me, however, after six months of poring over Kafka's unfinished manuscript of "The Trial" and its painstaking transcription, published in 1997 by Kafka scholars Ronald Reuss and Peter Staengle as a collection of largely unordered notebooks. One can see why Kafka experts grumble about what they see as the misuse, even abuse of "Kafkaesque." In 1991, the New York Times got Kafka biographer Frederick R Karl to provide a more insightful, but also more limiting definition:

What's Kafkaesque is when you enter a surreal world in which all your control patterns, all your plans, the whole way in which you have configured your own behavior, begins to fall to pieces, when you find yourself against a force that does not lend itself to the way you perceive the world. You don't give up, you don't lie down and die. What you do is struggle against this with all of your equipment, with whatever you have. But of course you don't stand a chance. That's Kafkaesque.

There's nothing in Karl's description about complexity, weirdness or even a lack of logic. Instead, Karl talked about coming up against an overwhelming force whose workings contradict the way in which one sees the world.

In that sense, few if any of the episodes to which the "Kafkaesque" label gets attached are worthy of it. If you see all bureaucracy as Kafkaesque, for example, you're misapplying the term because you claim an understanding of bureaucracy's nature and it fits comfortably into your worldview. And all the trials described as "Kafkaesque" feature both a specific accusation and a specific, transparent if wrongheaded goal pursued by the trial's organizers. That's more than could be said for the case of Josef K, the protagonist of "The Trial." Unlike, say, Navalny, who is pursued in various sadistically inventive ways because he's a danger to President Vladimir Putin's regime and knows full well what's going on, K has no idea what he's being accused of, let alone why, for what purpose or by whom. The onus is on him to figure out what's wrong and what's required to rectify things; he's given all kinds of hints and explanations, but they, too, come from people who have never been told anything clearly. That's a problem that also afflicts another K, the protagonist of "The Castle."

The inscrutable nature of power in Kafka's writings may be the reason real-life repressive regimes haven't hated or feared him as much as, say, George Orwell. While the latter wasn't published in the Soviet Union until its very last, almost-free years, Kafka broke through in 1964, when his stories were first published in a literary journal. He only fell into disfavor again after Soviet troops invaded Czechoslovakia in 1968: The censors saw a link between his work and the ill-fated Prague Spring. Official Soviet ideology and the underlying unofficial cynicism were arguably both far removed from the nebulous, elusive, dream-like nature of the Kafkian repressive authority; they had far more in common with Orwell's "boot stamping on a human face - forever."

What Kafka described in "The Trial" and "The Castle" was perhaps akin to the modern, much-ridiculed concept of a "deep state," a self-perpetuating caste of grey bureaucrats, a secret society with no clear goals or ideology except the well-being of its members. The views of today's conspiracy theorists are, in a way, close to the Kafkian worldview: What power does is incomprehensible to them, so they're willing to accept the wildest explanations.

Yet actual power in today's world, be it in democracies or autocracies, is loud and full of self-justification; it's inclined to use simple arguments, it's flashy and made-for-TV, and it's covered with a shiny patina of money, unlike the drab but inaccessible, subtly malicious but at times inexplicably brutal "judiciary" of "The Trial." Today's rules may sometimes be convoluted - but the world of "The Trial" doesn't even have clear rules for legal procedure; in that it resembles Orwell's Oceania, where laws couldn't be broken because there were no laws.

Then what is it that makes Kafka so relevant that his name keeps coming up every time a system seems unjust or rules illogical? It's something that lies under the surface of the writing and that, to me at least, is the source of sardonic humor in "The Trial." It's the universal passive acceptance of overwhelming injustice and total opacity. Everybody in "The Trial" plays by rules they assume, not by those that have been laid down. K has his rebellious flashes - he makes a sharply-worded speech during his first court appearance, he ignores a judge's summons and goes instead to see his mistress, he bravely fires a lawyer he suspects may be working against him, and even as his executioners lead him away, he resists them briefly. But by the end of the nightmare year between his 30th and 31st birthday, the flashes of anger are further between, briefer and more subdued. In fact, from the start, K is, if somewhat reluctantly, going along with the charade, just like everyone else around him.

The truly Kafkaesque part of living in a dysfunctional society is the sense that protest is dumb, futile or both, the recognition that direct confrontation is ineffective, flight is impractical and that the system ultimately has its reasons. Unjust trials and unfair rules are only possible because everyone tries to explain them away, to live with them, to not insist on resistance.

Kafka appeared to see this flaw in himself, too. At the very end of the translation, I had to catch my breath when I saw something in the manuscript that somehow didn't make it into the Russian and German editions I had previously seen. Just as K is about to die without putting up a final fight, Kafka suddenly slips out of his third-person narrative and into the first person. "I raised my hands and spread the fingers," he writes, as if it is he who is about to take a butcher's knife in the heart.

Intentional or not, this is a scary "I," one I kept in the translation as a reminder to myself not to give in to the Josef K in my head. It's not the mysterious power of the system that brings unfair trials to nightmarish conclusions, it's the Kafkaesque acquiescence of those who participate and those who look on. "The Trial" doesn't directly propose an alternative, but it's conspicuous by its absence: Fight back, even if you have to overuse the word "Kafkaesque" as you do. (Bloomberg)