Indigeneity is not a label, it’s a legacy- Bengal proved it

From Bankim to Bose, Bengal defined Indian identity not by origin but by contribu-tion, showing that true nativeness is earned through courage and conscience

Indigeneity is not a label, it’s a legacy- Bengal proved it

“If indigeneity is measured either by ancestry or by sacrifice, then Bengali stands as India’s tru-est indigenous soul moreover the community that gave the nation its conscience”.

In recent years the term ‘indigenous people’ has entered Indian discourse with growing confu-sion and discomfort. While globally used to protect the rights marginalized communities, in In-dia its careless application has begun to draw lines where none should exist.

If all are born of this soil, shaped by its rivers, languages, and histories then who is more indigenous than anoth-er?In a civilization as ancient and layered as India, dividing people by such terminology risks repeating the same, exclusion, we claim to resist. Calling one group ‘indigenous’ and others ‘Indian’ creates an unnecessary hierarchy of belonging.

India’s Constitution already upholds equality- no citizen is less native than another. Every culture within India, from Tamil to Meitei, from Pahadi to Bengali, has evolved within this land’s continuum of memory. To isolate one as original and others as later is to misunderstand India’s civilizational unity.

Even more troubling are the ignorant remarks that sometimes emerge in this divided language. People of the North-east for instance have often been wrongly labelled as ‘foreign looking’, an insult born of frac-tured thinking.

When the vocabulary difference takes root, prejudice follows. If in one country some are called “indigenous and other Indian” the result will only be alienation, not identity. India’s soul has never thrived on separation. It is plural, inclusive and indivisible.

Every citizen is equally Indi-an, by birth, by belonging and by contribution. Few regions illustrate this idea better than Ben-gal, a land whose people never asked to be called “indigenous” because they proved it through action.

Their belonging was earned not through terminology but through sacrifice. Between 1909 and 1938, official records from the Cellular Jail in the Andamans show that out of 585 political, 398 were from undivided Bengal, an extraordinary 68 percent (%).

These men and women came from every background, Hindu, Muslim, Dalit, Brahmo, and secular, yet were united in one truth, India was their only identity.

The story of India’s unity under one flag begins with Bengal’s renaissance. Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay, one of Bengal’s greatest sons, gave the freedom movement its first anthem, Vande Mataram, in Anandamath. Through Durge-shnandini and Kapalkundala, he infused literature with patriotism, showing that love of land could be a sacred act.

His founding of Bangadarshan Magazine gave Bengal a literary platform that transformed im-agination into ideology. Bankim’s vision transcended religion and caste, the motherland was everyone’s mother. At the same time, Bengali’s villages witnessed another kind of revolution, one of dignity and equality.

Harichand Thakur (1812-1878), spiritual reformer from the Na-masudra community, founded the Matua Mahasangha to challenge caste oppression. He preached that spirituality does not depend on birth but on character.

His son Guruchand Thakur carried the torch forward, organizing schools and social movements. His famous words, ‘Though beg, teach the child’ embodied the principle that education is the foundation of free-dom.

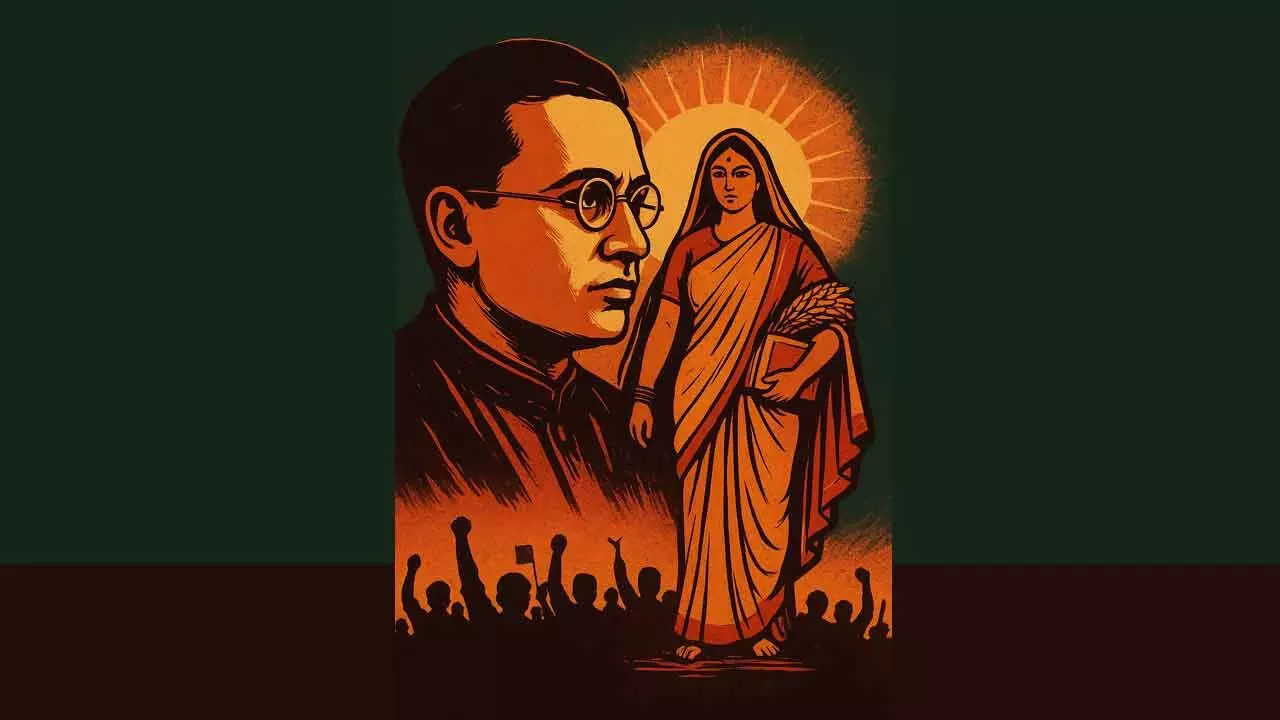

The Matua movement gave identity and respect to millions who had been denied both. Together, the Thakurs showed that the essence of being indigenous is not hierarchy but human-ity. In 1905, as Bengal faced partition, Abanindranath Tagore painted Bharat Mata, saffron-clad figure holding scriptures and grains.

The image united Indians across faiths and provinces, de-claring that the motherland was divine, not divided. This idea found voice in Rabindranath Ta-gore’s Jana Gana Mana (1911), later India’s national anthem, which celebrated the eternal guid-ing spirit of the nation, the unseen unity beneath its diversity.

Tagore’s Gitanjali echoed the same truth, that essence lies not in race or creed but in shared consciousness.

Swami Vivekananda gave voice to India’s confidence. He saw religion not as division but as discipline, a force for service and strength. His call for self-reliance inspired a generation of youth, who later built revolutionary groups such as Anushilan Samiti and Jugantar. Vivekanan-da’s message made one truth clear, India’s indigenous identity lies in moral courage, not in trib-alism or exclusivity.

Long before the Swadeshi Movement, Bengal had already become the crucible of rebellion. The Sanyansi Rebellion (1763-1800), beginning in Dhaka and spreading to Bihar, saw ascetics and peasants rise together against colonial greed.

Nearly a century later, the Indigo Revolt (1859-60) erupted across Nadia and Jessore, where farmers refused to grow indigo for British planters. Dinabandhu Mitra’s Nil Darpan captured their suffering and defiance, transforming economic resistance into moral theater.

It recognized that true knowledge is actionable Jnanam-Karma-sahitam knowledge joined with ethical work.These uprisings, though local in scale, kindled the spark of self-respect that would later illuminate the national struggle. Writers, teach-ers and reformers became chroniclers of courage, ensuring that rebellion was not silenced but sanctified in collective memory.

The Swadeshi Movement of 1905 triggered, by Bengal’s-by-Bengal’s partition, was therefore not a sudden awakening but a culmination of centuries of si-lent defiance. Boycotts, indigenous schools, and local industries reflected, the same conviction, that India’s strength lay in self-reliance and shared identity.

The spirit of Swadeshi was not merely anti-British, it was profoundly pro-Indian, proclaiming that every citizen, regardless of caste or region, was a stakeholder in the nation’s destiny. This revolutionary reached its zenith in Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose, Bengal’s indomitable son.

During World War II, when 45,000 Indian soldiers were captured by Japan in Singapore, Bose transformed them into the Indian National Army (INA), an army not of conquest, but of conscience. His thunderous call, “Give me blood, and I will give you freedom” resonated across Asia.

Under the call “Jai Hind”, he united soldiers and civilians, Hindus and Muslims, men and women, under one tricolor of sacri-fice. Even after his mysterious disappearance, Bose’s ideals endured. When Jawaharlal Nehru ended his first Independence Day address with Jai Hind, it was not mere tribute, it was a salute to the spirit of Bengal, the land where rebellion was born and nationalism refined.

If we look through Bengal’s lens indigeneity is not a label, it is an act. It is not something one claims by origin but earns by contribution. The peasant who rebelled in Dhaka, the poet who sang in San-tiniketan, the reformer who taught in Barisal and the soldier who fell under the INA flag, all were equally indigenous because all were equally Indians.

To call some Indians indigenous and others merely Indian is to betray that heritage. Bengal’s history teaches that belonging is not inherited, it is created, defended, and shared, India does not need new categories of Identity, it needs remembrance of the unity written in its struggles, sung in its songs, and sanctified in its sacrifice.

In the story of unity, Bengal, remains not a province but a pulse, the living heartbeat of India’s indigenous spirit.

(The author is Social Reformer and founder of Bongo Bhashi Mahasabha Foundation)