How UK-EU Deal Turns Page On Brexit – And What Happens Next

It is only beginning of – potentially long – negotiations to thrash out details of closer cooperation in trade, youth mobility, energy

How UK-EU Deal Turns Page On Brexit – And What Happens Next

The looming negotiations will be relatively narrow in scope. The Withdrawal Agreement and the Trade and Cooperation Agreement still provide the basis for the EU-UK relationship. The UK is not compromising on its red lines of not joining the single market, the customs union or allowing free movement of people

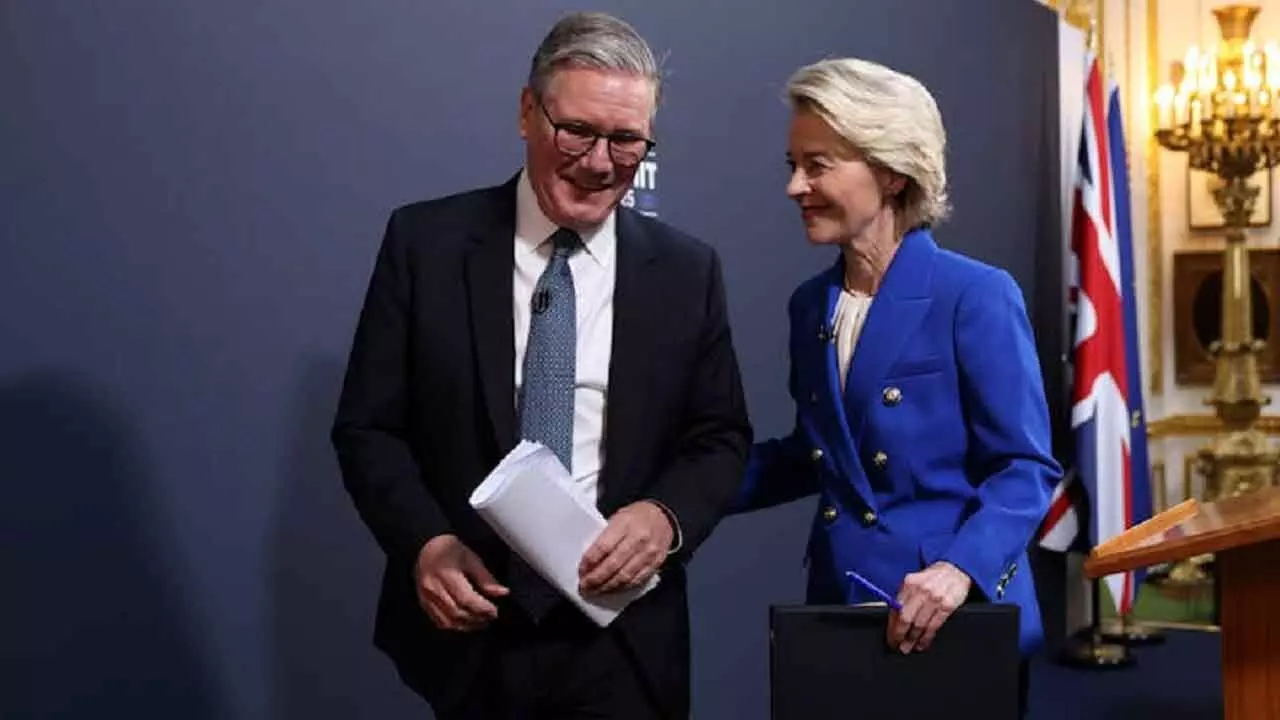

At their first bilateral summit since Brexit, UK and EU leaders set out a range of areas where they will seek to forge closer ties. European Council President António Costa, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen and British Prime Minister Keir Starmer hailed the agreement as a historic landmark deal that opens a new chapter in the EU-UK relationship.

But it is only the beginning of – potentially long – negotiations to thrash out the details of closer cooperation in areas like trade, youth mobility and energy.

As the two parties sit down at the negotiating table, they will, for the first time since Brexit, agree on how to make trade and cooperation easier. For example, one anticipated agreement will align UK food safety and animal health standards with those of the EU, thereby removing the need for most border checks and ease the flow of agriculture and food products between the two parties. And the expected youth mobility scheme will allow young people to travel, work and study in the EU and the UK for a limited period of time.

The looming negotiations will be relatively narrow in scope. The Withdrawal Agreement and the Trade and Cooperation Agreement still provide the basis for the EU-UK relationship. The UK is not compromising on its red lines of not joining the single market, the customs union or allowing free movement of people.

The negotiations will consequently not fundamentally alter the current relationship. While the impact of the agreements may be significant for specific sectors, the overall economic impact is expected to be relatively modest.

This is not to say that the upcoming negotiations will be easy or void of controversies. Over the next months, negotiators will have to agree on quotas, time limits, exceptions and financial contributions. Compromises and trade-offs will have to be found.

There will be domestic resistance on both sides. Concerns have already emerged that France might oppose the participation of British defence companies in EU defence procurement programmes.

And in the UK, critics argue that the decision to dynamically align UK rules and standards with those of the EU in certain sectors will make the country a rule-taker once again.

But the answer to the question on many people’s minds: “Will this bring us back to all those years of difficult and protracted Brexit negotiations?” is no – this time around, things are different.

In comparison with the Brexit negotiations, these negotiations should be far easier and swifter. They are less consequential and backed by strong political will from both sides.

Recent polling indicates that both Britons and EU citizens favour a closer relationship between the UK and the EU.

The agreement reached at the summit is seen as the first concrete manifestation of Starmer’s long sought-after reset of the relationship.

Moving on

The Brexit negotiations focused on establishing less cooperation compared with when the UK was a member of the EU. It was a question of addressing increasing barriers to trade and cooperation – something many perceived as a lose-lose situation. The upcoming negotiations, on the other hand, are seen to lead towards a win-win reset of relations. The parties enter the negotiations with a mindset of finding solutions that increase trade and facilitate cooperation.

The UK is now negotiating as an independent, sovereign country. During the Brexit negotiations the UK was an EU member (or a closely aligned former member in the case of the negotiations of the Trade and Cooperation Agreement).

It was thus important for the EU to make the benefits of membership clear and to discourage other members from leaving. As a result, it drove a hard bargain and the UK had limited influence on the negotiations.

However, unlike the UK – where Brexit has never fully disappeared from the political debate – the EU moved on quickly after Brexit. In Brussels, many now consider the UK an independent but like-minded strategic partner.

This is seen not least in the area of security, where the two parties agreed on a security and defence partnership. They set out a framework for closer cooperation in areas of joint interest, such as sanctions, information sharing and cybersecurity, and allowing them to better respond to shared global challenges and uncertainties.

Zooming out, the geopolitical picture has changed dramatically since the Brexit negotiations. With the war in Ukraine and the resulting instability in Europe, combined with the shifting priorities of US foreign policy, there is now an even greater need for EU-UK cooperation.

(The author is from University of Westminster;

Courtesy: The Conversation)