VB G Ram G aims at rural development with a future-ready strategy for growth

Strategic skilling, inclusive social security regime, micro-entrepreneurship key to reduce unemployment

VB G Ram G aims at rural development with a future-ready strategy for growth

Article 41 of the Constitution of India states: “The State shall, within the limits of its economic capacity and development, make effective provision for securing the right to work....” In the Constituent Assembly, there was a strong difference of opinion between those who were influenced by socialist ideals who wanted the right to work included as a fundamental right, and the strong capitalist lobby who opposed it.

Ultimately, it was included in the Directive Principles of the Constitution. Dr BR Ambedkar had described this as a “novel feature”, asserting that though these Directive Principles were not justiciable, they were to be considered as “instruments of instruction" for lawmakers and as “essential for economic democracy”.

The central and the various state governments provide assistance to the unemployed through various financial, skill development and employment generation programmes.

At the national level, they include the Prime Minister‘s Employment Generation Programmme (PMEGP), which provides margin money subsidy for bank loans for setting up microenterprises in the non-farm sector, the Pradhan Mantri Mudra Yojana (PMMY), which provides start-up funding for assistance for setting up businesses and the Deen Dayal Upadhaya Grameen Kaushalya Yojana (DDU - GKY), a part of the National Rural Livelihoods Mission (NRLM), which is focused on adding diversity to the income of rural poor families and catering to the career aspirations of the rural youth.

Another initiative, the Pradhan Mantri Kaushal Vikas Yojana (PMKVY), standardises skills, encouraging an aptitude towards employable skills by giving monetary awards and rewards, providing quality training to them.

The Nurturing Aspirations through Vocational Training for Young Adolescent Girls (NAVYA), another scheme, provides vocational training to adolescent girls and empowers them with skills for jobs in sectors like digital marketing and artificial intelligence.

The National Career Service (NCS), is a portal of the government of India for job seekers and employers for providing career guidance through counselling, vocational guidance and skill development, to bridge job-seekers and employers.

Traditional employment exchanges have, therefore, been transformed into IT-enabled career centres for holistic career development.

There are, in addition, state - specific portals with survey platforms for job, searching by category, location and salary. An example of a state government programme to assist intelligent, educated and talented persons by providing financial assistance till they get jobs is the Berojgari Bhatta Yojana of the Uttar Pradesh government.

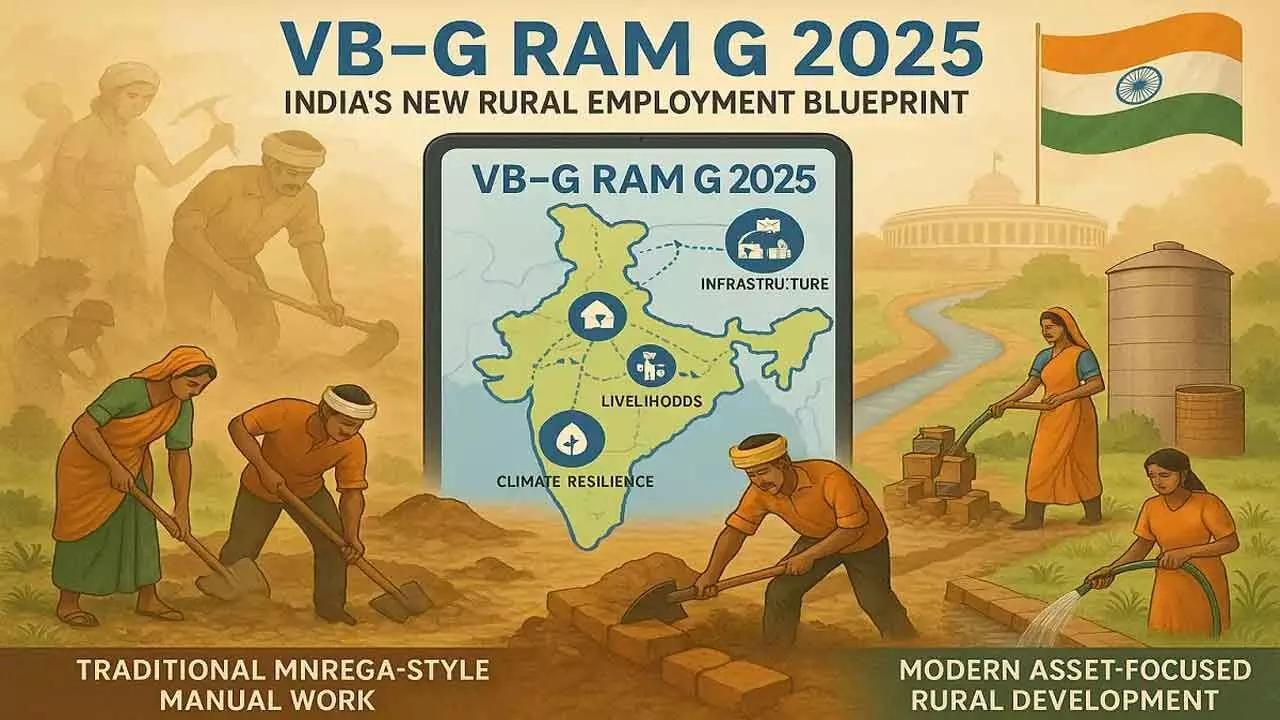

The government of India has now successfully piloted the passage of an enactment by Parliament that has replaced the MGNREGA. Called the Viksit Bharat Guarantee for Rozgar and Ajeevika Mission (Gramin). It is a new framework aimed at fulfilling the Viksit Bharat 2047 vision, by bringing in a transformation in the sphere of rural development with a future-ready strategy.

The programme promises an exciting mixture of many features, such as a link with the PM Gati Shakti Programme, a model digital governance framework that incorporates biometric authentication, GPS and mobile-based monitoring, real-time dashboards, proactive disclosures, and Artificial Intelligence tools. It also seeks to establish, at the national and state levels, Grameen Rozgar Guarantee Councils, as well as Steering Committees to oversee implementation.

The new programme, however, is viewed in some quarters as an attempt to altogether alter the fundamental character of the original scheme. They feel that it will reduce the size of development space to the states, making the central government the sole decision maker.

They point out that, over the last two years, only seven per cent of families could get the full quota of employment. It is also felt that the states may not show much interest in the scheme, both in view of their poor financial position, as also the increasing popularity of the Direct Cash Benefit schemes.

Experts also point out that the law stipulates conditions for eligibility and wage payment, despite ample evidence that such conditions, including poor connectivity, have victimized workers. Also, over two-thirds of workers belong to social categories protected by the Constitution. Any reversal of their rights, according to them, is tantamount to an attack on the Constitution.

The governments of Tamil Nadu and Kerala states had, in fact, already opposed it as one that undermines the interests of the states in the country; and that, despite the declaration by the central government that it will further the goals of Gandhiji’s idea of Rama Rajya, it serves little purpose, as diffused grassroots democracy is neither sought to be promoted or nourished.

Former Congress president Mrs. Sonia Gandhi has also pointed out that what was a rights base legislation, securing the right to work, has been virtually annihilated without any discussion or debate.

Restricting the areas of applicability, reducing the number of work days and leaving it to the discretion of the state governments to choose the period of its implementation and enhance the contribution of the state governments, according to her, are likely to significantly reduce the impact of the intervention. The changes, she points out, will also result in reflecting more of the central governments priorities than local needs.

Shivraj Singh Chauhan, Union Minister of Agriculture has, however, stoutly defended the new law which, incidentally, has since received the assent of the President, stating that the assumptions on which some have criticised it do not stand careful scrutiny, and a misreading of its substance and intent.

The plans at various levels, he points out, enable coordination, convergence and visibility across sectors, and do not override local priorities. Therefore, he points out, it is a process of renewal, grounded in experience.

At this point, it is necessary to note that the original scheme faced several challenges related to implementation and funding, as also a mismatch between goals and ground realities. Inordinate delays in payment of wages, payment of wages at a level lower than the minimum wage described in that area of by the state government, and of course, the usual corruption and leakages were rampant.

Creation of fake job cards and inclusion of fictitious names in the muster rolls also resulted in the siphoning of funds by middlemen and local officials.

As the Chairman of the Committee constituted by the government of Andhra Pradesh, in 2011, to enquire into the causes of the declaration, by certain farmers in East Godavari district of Andhra Pradesh, of a ‘Crop Holiday’, I had found that the scheme had caused a severe shortage of agricultural labour who used to come from backward areas looking for employment.

Some interesting suggestions have emerged from interested sources about how, going forward the fight against unemployment can become more effective.

One is the creation of formal employment opportunities in segments of the Fine Arts, such as dance, music, painting, singing, and sculpture, in addition to games and sports, all intended to facilitate remunerative self-employment.

Actively promoting and supporting barefoot professionals and technicians, for healthcare and maintenance services in the rural areas, is another concept that is being put forth.

A recommendation meriting serious consideration, in that context, and made from informed sources, is that India should adopt the “street stall economy”, whose development was encouraged by the government of China in the post-Covid era as a flexible and low - barrier form of self-employment.

Strategic skilling, an inclusive social security regime, promoting micro-entrepreneurship, and putting in place an improved regulatory ambience to transform flexibility into sustainable careers are some measures that can aid that effort. Initiatives to empower the youth, women and informal workers and ensuring that technology-driven efficiency benefits everyone and not just establishing platforms, are some more measures that can strengthen that effort.

The phenomenon of gig workers, therefore, would appear to be a bit of a double-edged sword. However, it does offer itself as a useful instrument, which, if wielded skilfully, can become an important part of the future strategy for building a robust economy characterised by sustainable and equitable development and rapid growth.

So we come, once again, as in Part I, to the end of this piece. On the rather serious issue of unemployment. And, to sign off the discourse on a light hearted note, here is a story I heard. There was this highly attractive job, for which applications had been invited through a newspaper advertisement.

One of the applicants, who lived in Mumbai, rang up the agent of the potential employer at the number given in the ad. He had ready answers to all the questions posed and was asked to come over to Kolkata immediately. “But”, he protested, “The ad gives a local address.” “That”, the agent explained patiently, “Is because the queue for the interview starts in Bombay!”

(The writer was formerly Chief Secretary, Government of Andhra Pradesh)