India should embark on year-wise phase out of chemical fertilisers

Despite less use of fertilisers, UK records impressive crop yields

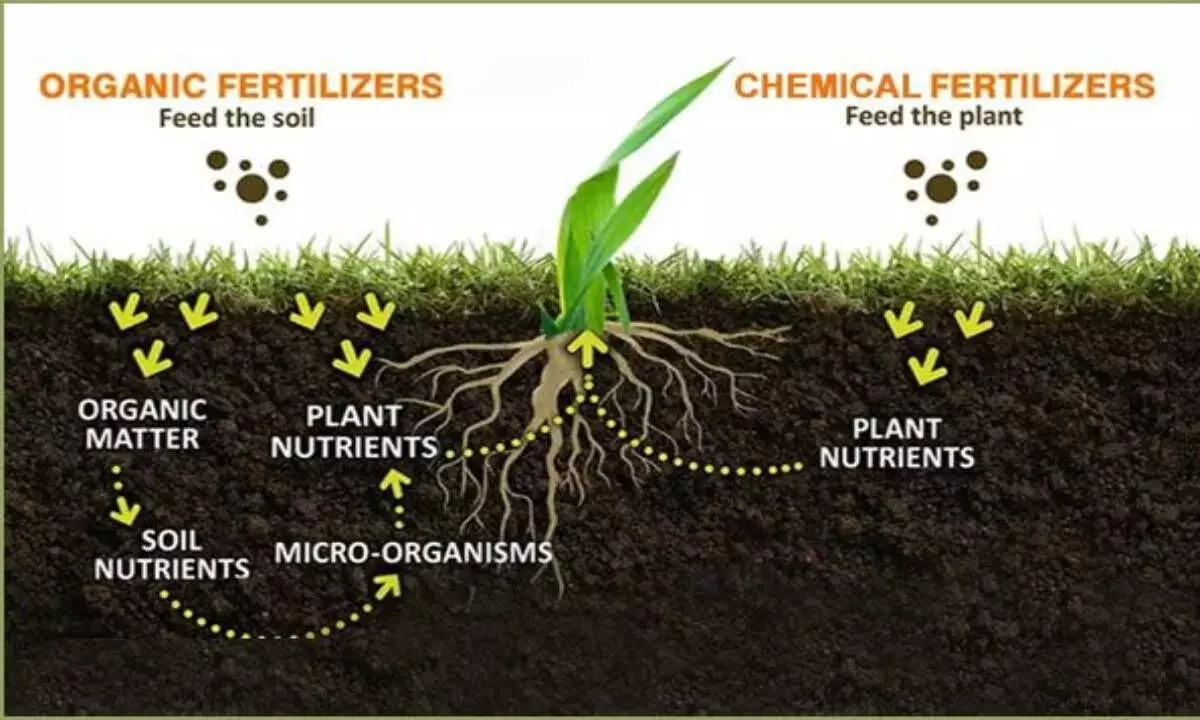

image for illustrative purpose

It may sound incredible. Crop yields have gone up in the United Kingdom (UK) despite a visible decrease in fertiliser use.

Not many agricultural scientists will believe these figures. Nor will the policy makers. But the latest report of the UK’s Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) should at least help the international community to press the reset button for ushering in a true transformation of the food systems.

The Defra study shows an increase of 2.4 per cent in the crop productivity of four crops – wheat, barley, oilseed rape and sugar beet – despite a drop in fertiliser application by 27 per cent when compared with the average usage over a decade, between 2010 and 2019.

Ascribing a rise in fertiliser prices to be the main cause behind the decline in its use, The Guardian (July 28, 2023) reports that with natural gas prices rising in the wake of the Russia-Ukraine conflict fertilise prices had increased three times. A steep rise in fertiliser prices forced farmers to reduce its application.

This eye-opening study comes at a time when excessive use of chemical fertilisers in Punjab, considered as India’s food bowl, has brought the soil fertility down to almost zero thereby reducing the crop yields. Indian parliament was recently informed that despite an increase in fertiliser application by 10 per cent over a period of five years, from 2017-18 to 2021-22, Punjab has seen a decline in 16 per cent in wheat production and 17 per cent in wheat yield.

Similarly, the UK study too had shown that notwithstanding a 10 per cent increase in fertiliser application for potatoes, the yield dropped by 8.6 per cent.

Punjab and Britain are situated miles apart. But the two studies coming from two different parts of the world, when seen in tandem, point to an urgency to move towards a sustainable transformation based on a year-wise phase out plan for chemical fertilisers. Keeping eyes widely shut and thereby ignoring the warnings will not only come in the way of achieving the ambitious targets under the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) but also show how the society, as a whole, has buckled under the dominant narrative led by corporate agriculture advocates thereby not only destroying the environment but also exacerbating the climate crisis.

As The Guardian report points out, based on earlier studies by Defra, fertiliser being a major cause of pollution, nearly 50 per cent of nitrate pollution, 25 per cent of phosphorous and 75 per cent of sediment pollution comes from agriculture. This is true not only for Britain, but is a universal problem as well as a limitation in sustainable development. In fact, the nutrient efficacy of fertiliser has been much lower in developing countries, and is further declining.

I thought the best way to restore soil fertility and build on soil health would be to encourage organic matter in soils. But not much enthusiasm has been seen and most projects to restore soil health have only received lip sympathy.

In India, a former Director General of the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) had acknowledged that while farmers could produce 50 kg of wheat by applying one kg of NPK fertilisers in the 1980s, its response measured in terms of crop production has come down to just eight kg by 2017.

If the latest Punjab studies are pointers then the trend has only worsened. Everyone believes that we should restore soil health by reducing the application of chemical fertiliser. However, every year we see a rise in fertiliser subsidy. This gives an indication of the huge disconnect in what the policy makers say and finally end up doing. Put together, domestic fertiliser productions as well as its imports have actually been increasing.

Several reports have shown how the fertiliser companies raked in mega profits in recent years. Nine of the major fertiliser giants have walked away with profits of $ 57 billion in 2022.

At the same time, these fertiliser companies are not letting go of their control over the transformation being sought in the food and farming systems. Much of the power is being asserted through the control the companies exercise over agricultural research systems where scientists still continue developing high-yielding crop varieties in response to chemical fertiliser and pesticides. Although public attention has, over the years, shifted to healthy soils and healthy foods, dominant farm research systems haven’t yet responded by redirecting the university research to focus on agro-ecological farming systems and crop breeding responding to organic matter.

Reducing fertiliser application by a quarter of its normal usage and still recording a significant increase in crop production, as the UK study shows, is an illustration that should help reform agricultural research.

But I doubt if Defra itself will reorient its agricultural research programmes to be based on reducing fertiliser usage and building up soil health in the process. Past experience has shown that the need to fix the broken food systems, as many have pointed out, is actually being resisted by the bureaucracy. Whether it is in UK or India or for that matter any other developing country, it is invariably the bureaucracy that comes in the way of a healthy food and farming transition.

This is primarily because of the huge gaps and lapses in the training and reorientation programmes for the bureaucracy. They have rarely been exposed to the diverse farming system that exists in the country. I have never understood why the mid-career bureaucrats should be sent to universities abroad for training. Why can’t they be deputed to spend time with rural communities within the country where at least they are exposed to the ground realities? Similarly, I don’t see any reason why progressive farmers, who are otherwise trendsetter in agro-ecology, cannot be part of the visiting faculty of any agricultural university? Why should the ICAR or other agricultural universities think they alone carry the wisdom to transform agriculture?

Traditional knowledge, know-how and skills should not only be documented but also applied. Research programme should focus on vetting the know-how that is time tested and has been sustained over the generations.

The time for following the one-way route, from ‘lab to land’ is gone. It is now the time to learn from the people and draw from the immense wisdom that somehow lies hidden and buried. It is the farmers who carry the wisdom and not a few people sitting in the corporate board rooms.

If the world has to move towards any meaningful transition in food and farming, it is time to reverse the research and development focus from ‘lab to land’ to ‘from land to lab’.

(The author is a noted food policy analyst and an expert on issues related to the agriculture sector. He writes on food, agriculture and hunger)