Adopt Kerala Model To Lessen Farmers’ Plight

Adopt Kerala Model To Lessen Farmers’ Plight

Since 2020, Kerala has launched a price stability programme for fruit and vegetable growers. It has worked out the cost of production for 16 fruits and vegetables. In addition, a base price that includes 20 per cent profit has been fixed. Whenever prices fall below the benchmark prices, the state government steps in. To ensure price stability and market access, procurement and marketing of fruits and vegetables have been appropriately organized. This approach has helped provide livelihood support to 4 lakh farmers

The emotional response that the Union Agriculture Minister, Shivraj Singh Chauhan, expressed the other day by reaching out to Maharashtra’s groundnut farmer Gaurav Panwar whose crop was washed away in the mandi, is certainly laudable. In a video clip that went viral, the distress on the face of the groundnut farmer who was trying to gather his drenched harvest after unusual heavy rains poured over drew a lot of concern, sympathy and even empathy from the viewers.

Expressing compassion for the poor farmer, Shivraj Singh was probably overcome with compassion and he decided to speak to the farmer, assuring him that his loss would be compensated by the State government.

Wonderful gesture that needs to be applauded.

“Sad state of affairs despite nearing 8 decades of Independence .. The farmers have been facing all kinds of problems. No MSP, No guarantee of crop, humiliation, starvation what not? You name it farmer faces it.. So the Governments must be sensitive to their problems. Maharashtra farmer Gaurav Panwar on his knees in a muddy mandi compound, using his bare hands to gather his drenched harvest (groundnuts) during unseasonal rains,” wrote a citizen Dr Srinubabu Gedela on X (earlier Twitter). The pain and anguish that Dr Gedela expressed on the micro-blogging site conveyed the harsh reality under which farmers somehow continue to operate.

The depressing video had also pained me.

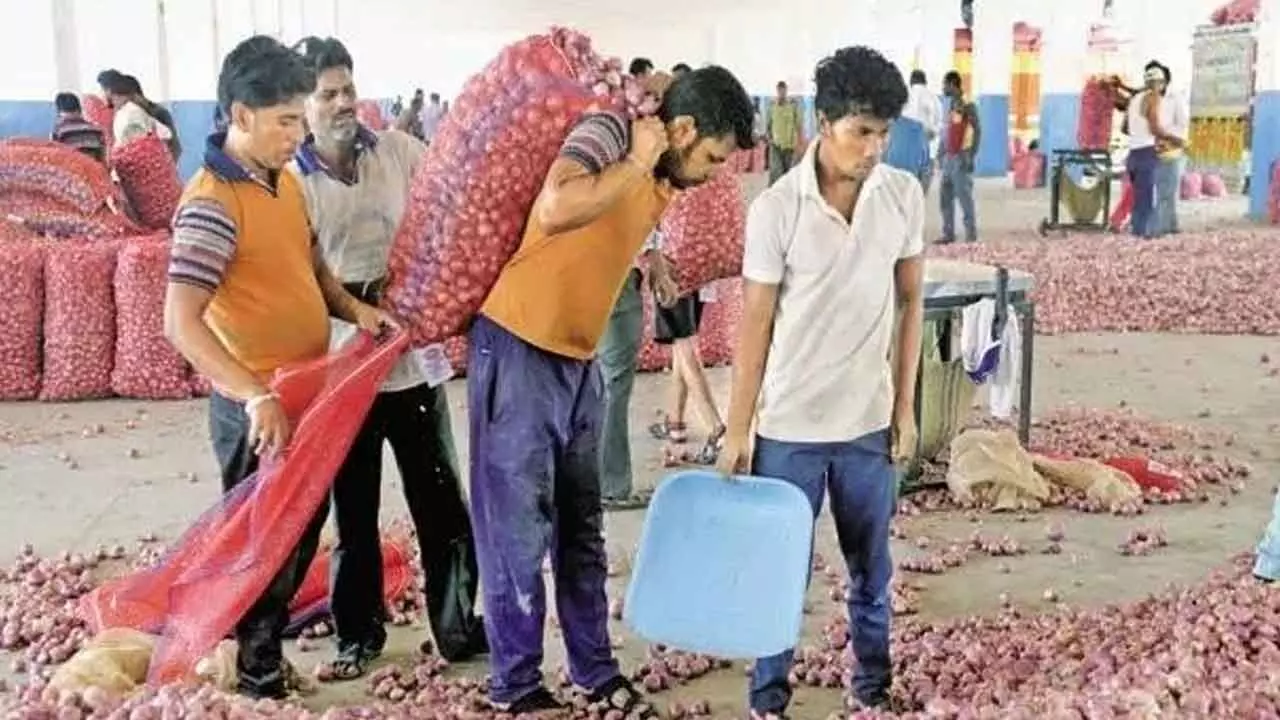

A few days later, I saw another video in which a distraught Maharashtra farmer was shouting at the top of his voice, standing in a mandi, pleading with onlookers to buy his onion crop for as low as Re 1 per kg. “Please help me recover the transportation charges I have paid to bring the produce to the market.” I am not sure how much he was finally able to recover but somehow felt enraged why didn’t the video go viral. Perhaps, the Union Agriculture Minister, too, would have felt the pain and expressed his willingness and ‘duty’ to compensate him also.

During the same week, another video report in the News Potli web portal, showed the devastation that a Kushinagar farmer in Gorakhpur district had undergone when severely strong winds had uprooted his banana plantation that he had grown in a leased plot for which he had paid Rs 1 lakh. If the storm had not run over his crop, he was expecting a return of Rs 4-lakh. As per the field report, nearly 300 farmers in the region were left devastated.

As if this was not enough, a retired agricultural scientist from Haryana Agricultural University, Hisar, came to see me yesterday. He had a video of his tomato crop lying stored in his house. He said he was not able to find buyers for his crop not even willing to pay Re 1 per kg, His plea was the same: “please get me buyers so that I can at least recover the cost incurred on plucking and storing the tomato crop.” As we all know, while his crop goes abegging, the retail price for tomatoes hovers around Rs 20 per kg.

And yet, I read a tweet (in Hindi) on Shivaraj Singh’s timeline. The video shows the Minister happily driving a tractor with the message escribed: “Khet main jab pasina behta hai, to dharati sona uglati hai” (literally meaning that when farmers sweat it out in the field, the fields produce gold.” I don’t know why the farmers that I mentioned above failed to cultivate gold in their fields. After all, you can’t produce a crop without sweating it out but why is that a lot many farmers suffer the consequences of crop failures and even price crash.

For over several decades now, I have shared the despondency and tragedy that farmers face when prices crash. I have often said it is not from plough to plate that we are given to understand but in reality what farmers end up with is: from farm to flop.

It’s only when stock markets crash that the entire government machinery gets in a war mode with ‘war rooms’ literally springing up in the first few days to minimise the financial losses for investors. It looks as if the country has been hit by a nuke. But when it comes to farmers, no one seems to be bothered, not even remotely concerned.

For decades, as I have said earlier, I watch with regret the plight under which farming operates. With successive governments failing to build and strengthen existing farm infrastructure, and with the entire focus being left to building highways, farmers are left in the lurch. For any economically sensitive government, the priority should be to rebuild agriculture, providing adequate public resources to compensate farmers with disaster relief. But I haven’t seen this happening over the several past decades. It is only when a political party is in the Opposition, a lot of sensible promises are made, only to be forgotten once the party gets into power.

Although I don’t see any silver lining in the dark clouds that hover over agriculture, I still would dare make a suggestion. Instead of promising to compensate a farmer for the crop losses he has incurred, why not rescue the entire farming community that faces recurring losses. The volatility in prices of perishables like fruits and vegetables, which have led to prices slumping routinely, needs to be addressed drawing a leaf from Kerala’s unique ‘base price’ formula that assures at least a minimum price for the farmers good enough to cover his cost of production plus a profit share of 20 per cent. This is the least any government can do to see that farmers are not ruined when market prices fall. Since 2020, Kerala has launched a price stability programme for fruit and vegetable growers. It has worked out the cost of production for 16 fruits and vegetables. In addition, a base price that includes 20 per cent profit has been fixed. Whenever prices fall below the benchmark prices, the state government steps in. To ensure price stability and market access, procurement and marketing of fruits and vegetables have been appropriately organized. This approach has helped provide livelihood support to 4 lakh farmers.

It began in 2020 with an outlay of Rs 10 crore. Over the past 5 years, state support was required when prices of certain vegetable fell in certain districts. The budgetary allocation has meanwhile gone up to a little over Rs 32 crore. I see a twinkle in the eyes of Dr Rajasekharan, Chairman of the Kerala State Agricultural Prices Board, when he tells me how the base price mechanism has been able to largely address the agrarian distress that is clearly visible.

If Kerala can show the way, I see no reason why the programme cannot be lapped up at the national level. Instead of shedding a tear or two before the cameras, the effort should be to wipe out every tear from the face of farmers.

(The author is a noted food policy analyst and an expert on issues related to the agriculture sector. He writes on food, agriculture and hunger)