The role of education & health in bridging the inequality gap

Quality employment opportunities and sources of income are simply out of thereach for our major chunk population for lack of quality education and skills

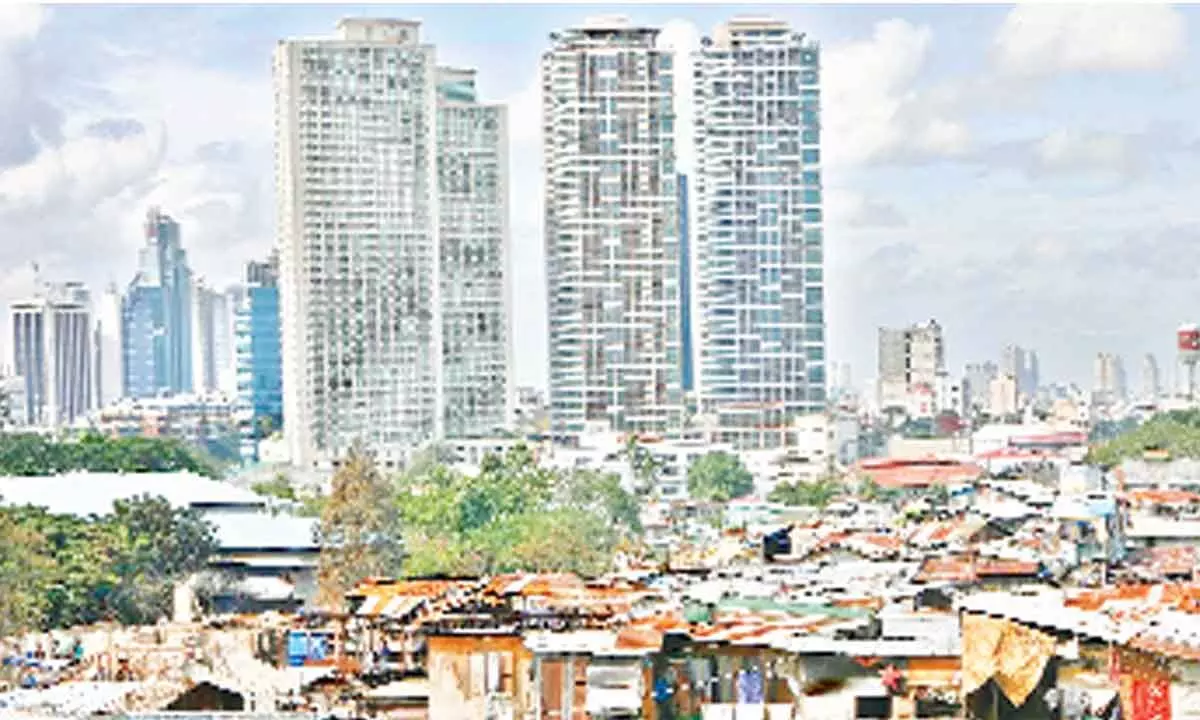

image for illustrative purpose

It is not so depressing at all but is certainly not something to cheer about! After 75 years of Independence marked by concerted pursuits to build an inclusive society, what 'The State of Inequality in India Report' recently released by Dr Bibek Debroy, Chairman, Economic Advisory Council to the Prime Minister (EAC-PM), suggests is not only a food for thought for the policy makers but also a reason to pause, reflect, act and correct suitably. The report has been written by the Institute for Competitiveness, a private sector initiative dedicated to purposeful dissemination of the body of research and knowledge on competition and strategy. It presents a holistic analysis of the depth and nature of inequality in India having compiled information on inequities across sectors of health, education, household characteristics and labour market. An official note quotes Dr Debroy stating that "inequality is an emotive issue. It is also an empirical issue, since definition and measurement both are contingent on the metric used and data available, including its timeline." He further added: "To reduce poverty and enhance employment, since May 2014, the Union Government has introduced a variety of measures interpreting inclusion as the provision of basic necessities, measures that have enabled India to withstand the shock of the Covid-19 pandemic better." Kudos to Dr Debroy for his great words, indeed!

'The State of Inequality in India Report' consists of two parts – Economic Facets and Socio-Economic Manifestations. It takes into account income distribution and labour market dynamics, health, education and household characteristics. The sources of data are the various rounds of Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS), National Family and Health Survey (NFHS) and UDISE+. The report moves beyond the wealth estimates that depict only a partial picture to highlight estimates of income distribution over the periods of 2017-18, 2018-19 and 2019-20. Though efforts are afoot to provide functional toilet and drinking water facilities in the school premises in rural and semi-urban areas, one wonders how resilient these will be. The Gross Enrolment Ratio has also increased between 2018-19 and 2019-20 at the primary, upper primary, secondary and higher secondary. According to NFHS-5 (2019-21), 97 per cent of households have electricity access, 70 per cent have improved access to sanitation, and 96 per cent have access to safe drinking water.

The report says, and we all will concur as well, that there has been a considerable improvement in increasing health infrastructural capacity with a targeted focus on rural areas. From 1,72,608 total health centres in 2005, the total health centres stood at 1, 85,505 in 2020. Whether these are enough to take care of nearly 135 crore people and about 70 per cent of them living in rural areas or not can be debatable, there is an increase of over 13,000 in their number in a period of 15 years is beyond any doubt. The report, taking note of the results of NFHS-4 (2015-16) and NFHS-5 (2019-21), says that 58.6 per cent of women received antenatal check-ups in the first trimester in 2015-16, which increased to 70 per cent by 2019-21. As much as 78 per cent of women received postnatal care from a doctor or auxiliary nurse within two days of delivery, while 79.1 per cent of children received postnatal care within two days of delivery.

The report admits that nutritional deprivation in terms of overweight, underweight, and prevalence of anaemia, especially among children, adolescent girls and pregnant women, remains areas of huge concern requiring urgent attention, while low health coverage, leading to high out-of-pocket expenditure, directly affects poverty incidences. Who are the worst sufferers? Certainly, the poor people whom we have segregated into different groups such as those who are educationally and socially backwards, those who have suffered untouchability and are now known as scheduled castes and scheduled tribes. Though there is no caste census, whatever empirical, primary or secondary data we have in our possession – officially or unofficially – they have their lion's share in the nation's population but not in national resources, facilities, opportunities and privileges. Even affirmative measures have not been able to improve their ease of life in general due to lack of accountability and transparency in their implementation at all levels and everywhere.

With a first-time focus on income distribution to understand the capital flow, the report emphasises that wealth concentration as a measure of inequality does not reveal the changes in the purchasing capacity of households. Extrapolation of the income data from PLFS 2019-20 has shown that a monthly salary of Rs 25,000 is already among the top 10 per cent of total incomes earned. It will be fair to presume that the share of those from deprived sections of society in this category of incomes earned will be next to nil. According to the report, the share of the top one per cent accounts for 6-7 per cent of the total incomes earned, while the top 10 per cent accounts for one-third of all incomes earned. The World Inequality Report-2022 (WIR) estimates that the top 10 per cent of the country's population account for 57 per cent of the national income, of which, 22 per cent is held by the top one per cent. There is no denying the fact that policy interventions, welfare and affirmative measures have failed to yield the desired results in addressing the chronic problem of income disparity.

'The State of Inequality in India Report' further informs that in 2019-20, among different employment categories, the highest percentage was self-employed workers (45.78 per cent), followed by regular salaried workers (33.5 per cent) and casual workers (20.71 per cent). The share of self-employed workers also happens to be the highest in the lowest income categories. The country's unemployment rate was 4.8 per cent (2019-20), and the worker population ratio was 46.8 per cent. Quality employment opportunities and sources of income are simply out of the reach for our major chunk population for want of quality education and skills. Most of them are engaged in unorganized sectors as semi-skilled or unskilled labourers. They toil to earn their livelihoods and are perennially deficient in resources and other wherewithal to improve their ease of lives. Notwithstanding all succour from the Central and state governments, they are caught in the vicious circle of 'hand to mouth' situation, literally having nothing to focus on the health and education needs of their wives and children. Hence, the need for better strategies to ensure uniform and quality education and health for all so that they are not deprived of their rightful share in well-paid job opportunities! Exceptions can never be at the core of policy formulations!

(The writer is a senior journalist, author and columnist. The views are strictly his personal)